Centralized Logging with journald and Standard Linux Tools

by Andrew Kroh

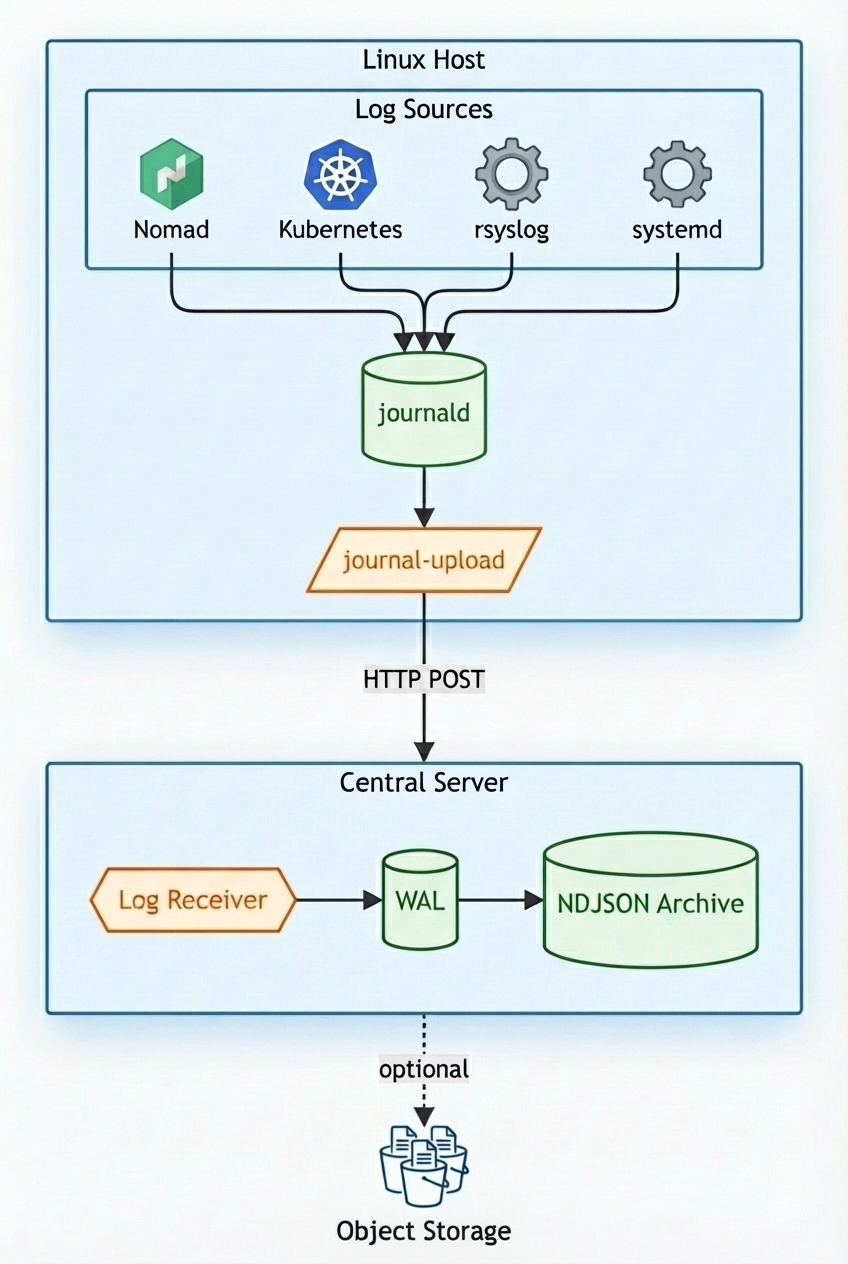

Every modern Linux distribution ships with journald as its logging system. It captures logs from system services, the kernel, and applications in a structured, indexed format. Rather than fighting this or replacing it with something else, I decided to embrace journald as the foundation of my centralized logging architecture.

The goal is simple: collect logs from all my systems into a central location, store them in a stable format that will be readable for years, and be able to load them into tools like Elasticsearch whenever I need to analyze them. No vendor lock-in, no proprietary formats, just plain JSON files on disk.

The architecture has three parts: getting data into journald, shipping it to a central server, and storing it durably.

Getting Data Into journald

Most applications already write to journald by default when running as systemd services. The interesting cases are containers and network devices.

Docker and Container Orchestrators

Docker provides a journald logging driver that sends container logs directly to the host's journal. Both HashiCorp Nomad and Kubernetes can use this driver. The key benefit is that container logs gain all the structured metadata that journald provides, plus you can add your own.

Here's how I configure a Nomad task to use the journald logging driver:

task "hello-world" {

driver = "docker"

config {

image = "akroh/hello-world:v3"

labels {

owner = "website@example.com"

}

logging {

type = "journald"

config {

tag = "${NOMAD_JOB_NAME}"

labels = "owner"

env = "NOMAD_ALLOC_ID,NOMAD_JOB_NAME,NOMAD_TASK_NAME,NOMAD_GROUP_NAME,NOMAD_NAMESPACE,NOMAD_DC,NOMAD_REGION,NOMAD_ALLOC_INDEX,NOMAD_ALLOC_NAME"

}

}

}

}

The tag option sets the SYSLOG_IDENTIFIER field, making it easy to filter

logs by job name. The labels option includes Docker labels as journal fields,

and env includes the specified environment variables. This metadata becomes

invaluable when you need to correlate logs across services.

When a container writes a log line, it appears in the journal with all this context:

{

"CONTAINER_ID": "0f07251e631e",

"CONTAINER_NAME": "server-c10085f7-a59f-4132-3f01-c9050a0303bd",

"CONTAINER_TAG": "phone-notifier",

"OWNER": "website@example.com",

"IMAGE_NAME": "docker.example.com/phone-notifier:v12",

"MESSAGE": "10.100.8.98 - - [18/Dec/2025:22:35:06 +0000] \"POST /v1/notify HTTP/1.1\" 200 598",

"NOMAD_ALLOC_ID": "c10085f7-a59f-4132-3f01-c9050a0303bd",

"NOMAD_DC": "va",

"NOMAD_JOB_NAME": "phone-notifier",

"NOMAD_TASK_NAME": "server",

"PRIORITY": "6",

"SYSLOG_IDENTIFIER": "phone-notifier",

"_HOSTNAME": "compute01.va.local.example.com",

"_TRANSPORT": "journal"

}

Network Devices via rsyslog

Network devices like switches, routers, and IP phones typically send logs via syslog over UDP. You can configure rsyslog to receive these and forward them into journald, preserving the original message and adding metadata.

Create /etc/rsyslog.d/10-syslog.conf:

module(load="omjournal")

module(load="imudp")

input(type="imudp" port="514" ruleset="syslog-to-journald")

template(name="journal" type="list") {

constant(value="udp_514" outname="TAGS")

property(name="rawmsg" outname="MESSAGE")

property(name="fromhost-ip" outname="LOG_SOURCE_IP")

}

ruleset(name="syslog-to-journald"){

action(type="omjournal" template="journal")

}

This configuration listens on UDP port 514, preserves the raw syslog message

without parsing it, and adds the source IP address as metadata. The TAGS field

helps identify the log path when you have other rsyslog configuration.

Getting Data Out of journald

The systemd-journal-upload service is a built-in tool that ships journal

entries to a remote server over HTTP. It runs as a daemon, watches for new

entries, and pushes them as they arrive.

The service maintains a cursor that tracks the last successfully uploaded entry. This cursor is persisted to disk, so if the service restarts or loses connectivity, it resumes from where it left off without duplicating or losing entries.

Install systemd-journal-remote (it provides systemd-journal-upload) using

your distro's package manager, then configure the upload target.

Create or edit /etc/systemd/journal-upload.conf:

[Upload]

URL=http://logs.example.com:19532

Enable and start the service:

sudo systemctl enable --now systemd-journal-upload.service

The HTTP Protocol

The upload service sends journal entries using a straightforward HTTP protocol:

- Endpoint:

POST /upload - Content-Type:

application/vnd.fdo.journal - Transfer-Encoding: chunked

The body contains entries in the

journal export format.

Each entry is a series of field-value pairs separated by newlines, with entries

separated by blank lines. Text fields use the format FIELD_NAME=value\n, while

binary fields use a length-prefixed format.

The chunked transfer encoding allows the client to stream entries continuously. When there are no more entries to send, the client completes the request and waits for acknowledgment before updating its cursor.

Receiving and Storing Logs

The systemd project provides systemd-journal-remote as a companion to the

upload service. It receives uploads and writes them into local journal files.

This works well if you want to query logs using journalctl on the central

server.

I use a custom receiver that takes a different approach. Instead of storing logs in the journal export format, it writes them as NDJSON (newline-delimited JSON) files. The receiver:

- Accepts HTTP uploads from journal-upload clients

- Parses the journal export format and converts entries to JSON

- Appends to a write-ahead log (WAL) and fsyncs for durability

- Periodically flushes the WAL to compressed NDJSON files partitioned by date and hour

The output is zstd-compressed NDJSON files organized by region and time:

logs/

region=va/

source=journald/

dt=2025-12-18/

hour=14/

events-019438a2-7b3c-7def-8123-456789abcdef.ndjson.zst

Filenames use UUIDv7 identifiers, which embed a timestamp and random component. This allows multiple receiver instances to write files concurrently without coordination, enabling horizontal scaling when needed.

Each line in these files is a complete JSON object with the original journal fields plus metadata like the source region and timestamp. This forms what's sometimes called the "bronze layer" in a data lake architecture.

Why NDJSON?

The archival format matters for long-term retention. NDJSON has several properties that make it ideal:

- Readable with standard tools:

zstdcat file.ndjson.zst | jq .works today and will work in 20 years. - No schema migrations: JSON is self-describing. Fields can be added without breaking anything.

- Open compression: zstd is open-source, well-documented, and widely supported.

- Easy to rehydrate: Decompress, parse JSON, bulk-load into Elasticsearch or any other tool.

- Extensible to cloud storage: The same file layout works on local disk, NFS, or S3.

This approach decouples collection and archival from analysis. You can bulk-load historical data into Elasticsearch whenever you need it, write custom scripts to process the JSON directly, or reprocess the archive with updated parsing logic years later. The data remains accessible regardless of how your tooling evolves.

References

Subscribe via RSS